Are our bootstraps really enough?

Mon 27 March 2017

Are Our Bootstraps Really Enough?

By Kate Hollingsworth – Social Worker Counsellor at Therapeutic Axis

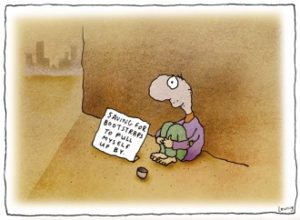

Recently, this Leunig cartoon caught my eye. It made me think about the concept of pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps to better our situation. The idea that if we just try hard enough, we have the capacity to change our circumstances. That we can overcome problems without any outside help. Therefore we should be able to overcome problems without any outside help.

Of course, even as I write this, I can think of many situations where it’s obvious that this idea doesn’t make any sense. No-one would expect a stroke survivor to recover without medical treatment and physical therapy. Nor would anyone expect an athlete to compete in the Olympics without support from a coach.

Yet somehow this notion that we should be able to manage life’s challenges and setbacks ourselves continues to pervade our individual and collective psyches. If we can’t do this, the problem lies with us. We internalise the problem. We aren’t tough enough, committed enough, good enough, clever enough…basically, we aren’t enough.

Unfortunately, this inability to resolve our difficulties can result in blaming and shaming, whether this is by other people, or ourselves. Many cancer patients are told to practice positive thinking as a means of fighting their cancer. When the cancer continues to progress in spite of this, feelings of blame and shame can arise, with the person believing it’s their fault because they’ve not been positive enough.

As a social worker and counsellor, I firmly believe that everyone has skills, strengths and inner resources which can be used for change and wellbeing. However, I am also concerned by the implications of this bootstraps mentality as it fails to acknowledge that people’s problems don’t occur in a bubble.

Human beings are social creatures. We belong to families, communities, larger society, and a global community. Within these systems, there are stressors and supports, social norms and values, all of which impact on a person’s wellbeing. I like to imagine that an individual is part of a hanging mobile. If you touch one part of the mobile, it will affect the other parts and vice versa.

Not every therapist works from this systemic perspective. Take anxiety for instance. Many therapeutic models treat anxiety as if it stems from within the individual. Treatment strategies include medication and cognitive and behavioural therapies designed to teach the person to think and/or behave differently. The responsibility for managing the anxiety lies with the individual, and if their anxiety doesn’t improve, it’s due to their shortcomings.

This is where I am trained to approach things differently. Not only am I interested in the client as an individual, but I’m also curious about the big picture that client’s life is located in. Do they have a good support network they can rely upon, or are they socially isolated? Are they from a socially/politically marginalised community? Do they have a sufficient income or are they struggling to make ends meet? Are they in stable housing or homeless? These social factors and many more can easily exacerbate an individual’s anxiety levels. It’s pretty straightforward really. If a person is living with a whole lot of stress and not much support then, of course, they’re more likely to feel anxious. This is why I don’t regard anxiety as being solely endogenous with no external contributing factors.

So what does this mean for the client who comes to me wanting help managing their anxiety? In a nutshell, it means I pay attention to the internal and external factors affecting a client’s wellbeing. I remember that difficulties occur within a context, not within a bubble. As a starting point, I work with the client to help them develop skills for managing and reducing their anxiety. Together we come up with strategies so that they are able to function within their social systems and not be as anxious. For some people, this is enough and that’s great. In every case, my job is to work with a client on what’s important to them. However, from a social work perspective, this is only part of the work.

Let’s go back to Leunig’s cartoon for a moment. Looking at the man, we notice that he’s not in the best of circumstances. Being a social worker, I want to know more about him. How has he ended up living like this? Why hasn’t he managed to improve his situation? What has happened to result in him having to beg for money? Does he have any income? If not, why not? Why has nobody put any money in his cup? Why does he think he needs to improve his situation on his own? Does he not have anyone he can turn to for help? Would he even be able to pull himself up by his bootstraps given his lack of shoes! How is it that in a first world country like Australia some people have enough access to resources and others don’t?

As you can see, once these contextual questions start being asked it becomes clearer that the solution is not as simple as him saving up the money to pull himself up by his bootstraps. He’s not starting from a level playing field in terms of privilege and power. We can assume that there’s some stigma attached to him being a beggar on the street. If this man was my client, the work would include working at a systemic level with the social structures impacting on wellbeing. What this would look like depends on the client, but the bottom line would be that I would shift the focus from his situation being solely his fault, and his responsibility to fix. I would consider how the other parts of the mobile either help or hinder his wellbeing. I would challenge those systems which perpetuate disadvantage and work to strengthen those that support him. To me, this is a social justice issue. Without consideration of how our social, political and economic systems affect wellbeing, we run the risk of perpetuating unhelpful systems and scapegoating individuals for not being able to resolve their difficulties.